By Chris Kelly (@ccalciok)

Welcome back. In the second part of our ‘Game Changers’ series, we move past the wartime period, focusing on two very different types of footballers. The first of which was, perhaps, the first to treat his position as a specialist one, assessing and adjusting his game and methods, and in doing so, somewhat revolutionising the position of a goalkeeper.

Lev Yashin

Lev Ivanovich Yashin, born in 1929, was given the nickname the ‘black spider’ for his incredible goalkeeping capabilities across a 20 year career, both domestically and internationally (while wearing completely dark attire on what was black and white TV screens at the time – thus leading to his aforementioned nickname) .

A one club man, Yashin spent his entire career playing for Dynamo Moscow, making 326 appearances in total as well as playing 74 times for the Soviet Union national team.

At 6ft 2″ tall, Yashin was a fair size for a goalkeeper of his time and was renowned for his presence and reading of the game allied with exceptional reflexes and agility.

What really set Yashin apart from other goalkeepers of that time however, was his command of his 18 yard box, his communication with – and manoeuvring round of – his defenders and his ability and willingness to come off his goal line to affect play. At a time when goalkeepers rarely showed this kind of authority and responsibility, Yashin’s skillset was unique and certainly revolutionary as we’ve seen how much more is expected of a goalkeeper as time has passed by.

Yashin is also credited with being one of the first in his position to start quick counter attacks with an early throw out and while still at a fairly primitive stage by comparison to today’s ‘sweeper keepers’, it’s widely believed that the dependencies and expectations of a goalkeeper began to shift with Yashin, and is therefore the reason he’s regularly mentioned as one of the most peerless goalkeepers of all time.

Due to his all round ability, his diligence to the needs of his position and the methods he implemented to carry out the role, Yashin remains the only goalkeeper to receive the prestigious Ballon d’Or award (in 1963), which is testament in itself to the high regard he was held and the impact he made on the game.

In terms of club honours, Lev Yashin won five Soviet League titles along with three domestic cup competitions. On the international stage, he was part of the Soviet’s European Championship winning side, finishing a runner-up four years later. Yashin also won Olympic gold for his country in 1956.

The individual honours he attained reflect his standing as arguably the games most decorated goalkeeper, winning nine European goalkeeper of the year awards alongside his 1963 Ballon d’Or success. Yashin, understandably, also won numerous individual accolades domestically and was recognised by FIFA as the ‘Goalkeeper of the Century’ in the year 2000.

After retirement, Yashin worked as deputy chairman of the Football Federation of the Soviet Union as well as undertaking administrative duties at his former club, Dynamo Moscow, though he sadly passed away at the relatively young age of 60 after losing his battle with stomach cancer.

However, the Moscow born shotstopper left behind an incredible legacy – putting the wheels in motion for the more dynamic and involved goalkeepers we see in today’s game.

Alongside his wonderful natural talent and attributes as a goalkeeper, Lev Yashin really did leave a lasting mark on his profession, changing the way a goalkeeper thought, acted and was perceived. In becoming almost like an extra defender with his ability to come out of his area to clear danger, Yashin’s talents allowed his teams to set up differently to most, playing a higher defensive line, initiating counter attacks and varying in tactical set-ups.

It is for both his extraordinary goalkeeping talent and his positional and game changing initiative that Lev Yashin will be revered timelessly and remembered for his effect on the sport of football.

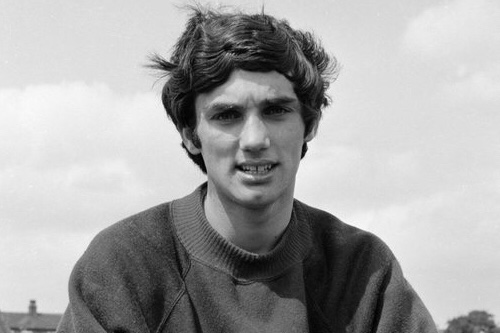

George Best

Northern Irishman George Best will need no introduction to followers of football, both young and old. Born in Belfast in 1946, Best is considered a 1960’s/70’s icon, both for his footballing ability and charismatic, fashionable persona – somewhat acquired through his on field talents and popularity.

Throughout his footballing career, Best was on the books of no fewer than 17 clubs, and though he became something of a nomadic figure in the latter half of his career, the 11 years spent at his first club – Manchester United – remain some of the most majestic, awe-inspiring and culturally captivating of any footballer to this day.

Growing up in the Northern Irish capital of Belfast, the winger played for local junior side Cregagh before being spotted by a Manchester United scout at the age of 15.

United were in the aftermath of the 1958 Munich air disaster, where 23 people tragically lost their lives (including eight Manchester United players) as the team travelled back from a European match in Belgrade.

Manager Matt Busby, surviving the crash himself, had been trying to rebuild the team and the club, focusing on bringing in talented young players from across the UK to take the place of the lost ‘Busby babes’ and get Manchester United up and running once more.

Despite struggling initially, missing the home comforts of Belfast, Best settled into a junior role at the club, where he’d train as a footballer alongside working at the Manchester Shipping Canal at a time when duties outside of the game were commonplace for young players looking to make the grade.

The young winger impressed Busby enough to earn a first team debut at just 17 years of age, facing West Bromwich Albion at Old Trafford in 1963, and he would go on to make over 20 appearances that season as United finished second.

Quickly making a name for himself, Best started to come in for some rough treatment from opponents. Showing resilience and strength to match his technical qualities, the ‘Belfast boy’ thrived under the pressure as he played a key role in United’s 1964/65 title win – a historic, emotional moment for the club following the seven years that had preceded it.

Best and his Manchester United team were coming of age. The following seasons however, would see the Northern Irishman gain iconic status and international superstardom.

After impressing immensely against some of Europe’s finest sides, Best would be given the nickname of ‘El Beatle’ (after the legendary band), with the view held that his sporting talents – alongside his character and looks – saw him in keeping with a new era, one brimming with fashion, excitement, music and colour.

Times were changing. After the lull and strict limitations that the second world war and the subsequent rebuild had brought, people were looking for more entertainment, experiences and fulfillment.

Technological advancements were aiding this along with an increase in personal wealth as communities, industries and the nation as a whole started to come away from the effects, both morally and economically, that war had made on them.

In general, people were a little more outgoing – maybe even brash – than previously and the era was certainly filled with more possibilities, optimism and chance-taking.

George Best epitomised this. A gifted genius with huge reach, pull and marketing ability – Best could be described as the first celebrity footballer, opening up restaurants and a nightclub in his adopted home city of Manchester.

On the pitch, he and United went from strength to strength, winning the 1966/67 league title before claiming the converted European Cup with a victory – inspired by Best- over Portuguese giants Benfica, culminating an incredible spell for the club after the harrowing events in Munich a decade earlier. George Best would also end the season with two individual awards – the Football Writers Association Player of the Year and the 1968 Ballon d’Or prize.

Best wouldn’t quite make the same impact on the international stage, largely due to the lower standard of his Northern Irish team mates and his his feelings that club football was were his challenges lye. The winger made 37 appearances for his country and is widely believed to be one of the best players to never play at a major international tournament.

Alongside Dennis Law and Bobby Charlton, Best guided United to further success before things slowly started to tail off for the club as they moved into the 1970’s.

Best was still performing superbly, able to glide with the ball on some very poor surfaces and maintaining his legendary status as one of the games greatest ever entertainers.

However, as his Manchester United team continued to progressively deteriorate on the pitch in the early 1970’s, Best started to get involved in disciplinary issues within the club, both in terms of behaviour and timekeeping, as well as numerous brushes with the law as both his footballing performances and life in general began to unravel somewhat.

Various managers, including Tommy Docherty and Frankie O’Farrell failed to address United’s slide, which ran parallel with that of the Northern Irish winger who, perhaps, was showing the affects of his lifestyle. Best had maybe overindulged in the champagne, playboy lifestyle his talents – along with the cultural shift of the era – had been afforded to him.

He had become more celebrity than footballer, unable to manage outside influences and all to often seduced by the bright lights and social standing he’d acquired.

His final appearance for Manchester United was on New Year’s Day, 1974 – a campaign which would ultimately end in a somewhat infamous relegation (to the second tier) for the club.

Best would go on to play for many other clubs, most notably Fulham and Hibernian along with a spell in the United States with Fort Lauderdale Strikers, Los Angeles Aztecs and San Jose Earthquakes. He would also make limited and sporadic appearances for clubs in South Africa, Ireland, Hong Kong and Australia before ending his career with a solitary appearance for Tobermore United in his homeland in 1984.

Through his life and times, George Best had gone from a shy, Belfast youngster to global superstardom and all the opportunities – and pitfalls – this presented him with.

The 1960’s generational change and Best’s almost peerless, certainly genius, footballing abilities had proved a perfect – yet ultimately toxic – mix, encompassing the good and bad effects on people in the public eye at that time.

Opportunities and exposure was there in abundance but, perhaps, education surrounding these was not. George Best’s didn’t know his limits or acknowledge the dangers of succumbing to various temptations and in turn, his footballing career faded far earlier than it should have. Best, like his mother, struggled with alcoholism throughout his life and ultimately, after many health scares, this cost him his life in 2005.

For all his misdemeanours, his run-ins with police, his increasing disciplinary issues and a growing blase attitude to his responsibilities, the legacy George Best left behind will be a timeless one.

He was a magician on the pitch, often described by those that saw him play as a phenomenon. Though an attacking player by and large, Best had the complete football brain, seemingly able to fill any role effortlessly. Like with many geniuses – in all walks of life – Best was also flawed, succumbing to a lifestyle of womanising, alcohol and nights on the town which would ultimately be his professional and personal downfall.

One certainty though, is that George Best and the 1960’s (into the 70’s) go hand in hand. A time of colour, verve, personality and experiment – though somewhat lacking in forethought of the repercussions.

As Best said himself though, towards the end of his life, you hope people remember his football, his incredible skills, crowd drawing capabilities and edge of the seat joy he brought to many across a pulsating decade between the mid 60’s and 70’s.

By Chris Kelly (@ccalciok)